Lecture 16: Statistical Street Fighting - Information Hygiene

Yan Zhang

There are many ideas that are less “statistical”, not backed up by studies through academic journals, etc. but that we still feel are probably valuable for doing forecasting. I call these ideas “street fighting” skills to differentiate from “established” knowledge. They are a microcosm of the messiness of the forecasting skill itself. For the next couple of lectures, we will focus on these types of skills.

A long long time ago, people fought each other with sticks and stones. These days, people fight each other with numbers, which, while being less physically harmful, does hurt our understanding of the world in a way sticks and stones do not.

(Sometimes we fight each other with both stones and numbers.)

Therefore, how we deal with the quality of the limited information we obtain, which some people call “information hygiene,” has become a very useful skill. There are two big reasons this skill is especially important for forecasting:

- Forecasting (at least with our definition) is low-data and high uncertainty. With little data, the quality of the data we do have is critical. We still obviously should care about the information hygiene in high-data regimes, but at least in those situations the additional data gives you more overall information to use.

- While “expertise” is usually associated with knowledge, a very important functional part of expertise is being able to evaluate the quality of information. In our generalist treatment of forecasting (as opposed to, say, a political science course about political forecasting), we are frequently interested in forecasts about very messy real-world phenomena that we do not know very much about, so being good at judging the pieces of knowledge we pick up in an area where we are not experts is very important.

My personal approach is to understand the “lifetime” of a piece of information from the time it is created to the time it is consumed by me. This process is analogous to how some people like to think about how their food gets to them “from farm to plate.” While the boundaries can be blurry, I like to think about the formation of information as having 3 main phases:

- Creation: At some point, someone who was not me decided to answer a question for themselves, giving birth to a piece of information. How was this done? (For example, how did they set up an experiment? What was their methodology? What was their conclusion?)

- Transfer: this information then traveled from them to me. Did anything tamper with the information during this process? (For example, was the result exaggerated for me or reinterpreted for me when it got to my attention? Furthermore, is it possible that certain results, or even whole experiments, never got to my attention because people didn’t want me to see them?)

- Digestion: how did I handle the information when I got it? (For example, did I take the information as given? Dismiss it? Believe it more than I “should” have? why?)

Let me give an example of what these phases may look like:

- Creation: Bob gets hired by a climate activist group to prove global cooling exists based on rock data from California. Bob performs a decent experiment, with some statistical test and p-value analysis. The experiment finished, but…

- Transfer: … the p-value is sad, at 0.14, so Bob fudges some data, and the p-value magically becomes exactly 0.05. Then the study goes to 20 journals and gets rejected by all except for journal 12, which publishes it. Next day The Manhattan Times blasts “Global Cooling Proven Beyond Doubt” citing the study and it’s everywhere on Twitter. Their sworn enemy newspaper, the Chicago Tribute, puts out a counter-article saying “Controversial Global Cooling Paper DESTROYED By Facts and Logic.”

- Digestion: For political reasons, I tend to read the Manhattan Times. This study pops up, I read it, it seems to make a lot of sense, and I accept it without further question. I see the Chicago Tribute paper, decide it is probably a conspiracy theory without even looking at it, and go on with life.

There are many things to say about all phases of this pipeline. The main point I want to get across is that since there are so many things that can happen to the information by the time it gets to us, it benefits us to understand the process and to make adjustments. Right now, I will focus on one very useful concept that can help us with every phase of the process (and maybe other parts of life!).

Information Creation - How good is the study?

Let’s start out with a historical puzzle:

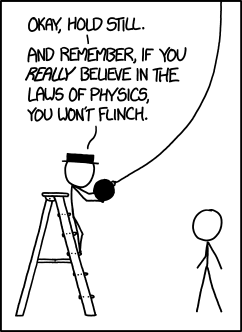

During WWII, the Statistical Research Group at Columbia University looked at aircraft that had returned from missions and collected data on which parts of the aircraft received the most damage (in red above). What should you do with this data?

While the initial reaction was to add armor to the places with the most red dots, Abraham Wald observed that the data gathering selected for aircraft that survived the missions. This means the red dots selected for places already good at taking damage. In a reversal to the intuition, Wald recommended adding armor to the places with the least red dots – those are precisely the places where hits seem to be correlated with the planes failing the mission!

These phenomena are generally called selection effects or selection bias. What does this have to do with information hygiene? Well, when the information comes from an experiment, the “creation phase” in my model of the flow of information is just “how the experiment was done.” Selection effects are pretty general and can be thought of as the cause of several subtle types of mistakes that can happen in the “creation phase” when doing experiments. In fact, many named statistical effects (such as sampling bias, survivorship bias, etc.) are just special cases of selection effects.

Here is some practice using actual studies that are relevant to selection effects.

- In an 1835 study, a physician gathered death certificates and calculated the mean lifetime associated with each profession. What was “the most dangerous job?”

- In a study on barroom brawls that resulted in death, what percentage of the time was the fight started by the victim?

Here are the answers. Hopefully they speak for themselves.

- Student, with the average age of 20.7.

- 90%; wonder who the police asked to get this information though?

I owe these examples to the pretty little paper A selection of Selection Anomalies. However, I only found this citation thanks to the excellent Teaching Statistics - a Bag of Tricks, which itself has many other illustrative examples about pitfalls when doing statistics.

Information Transfer - What are they trying to do to you?

Despite good intentions and even good experiments information is often corrupted or even changed by the time it gets to you in phase 2 (Transfer). Recall the example of Bob, who ran an experiment for a climate activist group: Bob’s experiment was fudged, and different newspapers chose to pick up different aspects of the experiment or tell the story in totally different ways. I like to think of this as a type of selection effect – different media outlets have different agendas and select for different types of information and packaging to present to us (the consumers of that information). Sometimes there is even a selection effect before the experiment is performed (for example, maybe the funder of the experiment is a lobbyist with a certain agenda).

To understand these types of effects better, I’ve found the following questions very important to ask myself:

Who told you this information? Why did they choose to give you this information? What are they trying to do with the wording of the information?

(Disclaimer: We would like to disclaim that we are really not trying to push a particular agenda here or say one of the narratives is “more right” than another even though we do have our own opinions. The point is that no matter if the goals are “right” or “wrong,” when writers present information they will write it in a way that serves their goals, so as readers it always helps us to be aware of these decisions the writers make)

(Disclaimer to the Disclaimer: you of course should also consider what my goals might be in writing the disclaimer above, and to decide for yourself how much you trust my words.)

As an example, consider the following excerpt from an article from TASS (a well-known Russian news agency). Try to look at specifics: What is the article trying to get you to think with a particular sentence? Why do you think the sentences are written the way they are?

Rally supporting Russia held in Sydney:The participants held Russian, Australian and Serbian flags as well as Putin’s portraits and banners with slogans against NATO’s presence near Russian borders A rally supporting Russia was held in Sydney, Australia’s largest city. According to a TASS correspondent, the rally held near the building of Russia’s Consulate General was attended not only by ethnic Russians but also by the representatives of other diasporas, including Ukrainians.The rally’s participants asserted their support for Russia and the people of Donbass as well as for Russia’s efforts on the denazification of Ukraine. They held Russian, Australian and Serbian flags as well as Putin’s portraits and banners with slogans against NATO’s presence near Russian borders.As Ksenia Trifonova, one of the rally’s organizers, told TASS, not only its participants wanted to express their solidarity with their homeland but also to urge Australia’s authorities to protect its Russian residents. “Many ethnic Russians live in this hospitable multicultural country, the majority of them are Australian citizens and we believe that there will be no place here for what is going in some other countries as we learned from the news, that we won’t see here threats and harassment on ethnic grounds,” she said, stressing that “it is very important to retain the operation of Russian media in foreign countries in order for people to see and hear another opinion on what is going on, this will help them understand Russians, understand our point of view.” …

Now, repeat the activity for the following excerpt from an article from Ukrinform, a Ukrainian news agency:

Regions continue to ask NATO to close sky over Ukraine… “Thousands of peaceful Ukrainians, including hundreds of children, died during this time. Houses and social infrastructure facilities – hospitals, educational institutions – are being destroyed in Ukrainian cities. All this was caused by attacks by Russian military aircraft and missiles, which are indiscriminately launched at Ukraine. The whole world sees the results of this barbarism,” Lviv Regional Council deputies said in their appeal.… Similar documents were approved by Zhytomyr City Council and Zhytomyr Regional Council. In a joint appeal, the heads of the regional military administration, the regional council and the city council of the regional center stressed that tonight the Russian troops bombed only the residential areas of Korosten and Ovruch. One person died, more than 30 families were left homeless. Both shelling incidents were recorded very far from military facilities.… “Arguments that the current refusal to introduce A2/AD is that NATO is trying to avoid a nuclear war are not convincing, as the Russian Federation has already started it. The historical lessons are difficult and must be taken into account. The decision to introduce the A2/AD zone over Ukraine will help save thousands of lives,” the document reads.Ternopil Regional Council also called for closing the sky over Ukraine. “The decision that will save hundreds if not thousands of lives is on your table. Do not shy away from historical responsibility to the world, your own peoples and the great European nation, which Ukrainians were and will be, and support our country in fighting the Russian occupiers for the right to exist,” the deputies demanded.… President Volodymyr Zelensky said that by refusing to close the sky over Ukraine, NATO leaders had given the “green light” to further bombardment of Ukrainian territory by Russian troops.According to the Ipsos poll, about 74% of Americans say the United States and NATO allies must close the sky over Ukraine.

More generally, some of the problems that can arise in the “transfer” phrase include:

- Maybe the statistician is biased in what results they want to have, so after they get some results they may run more experiments or change their stated goals until they found a result that they “want” to show you. (interested readers should look up “p-hacking” or “researcher degrees of freedom”)

- An organization (government, lobby group, etc.) can coerce the media to cover (or not cover) a statistical result in a specific way.

- If you are reading about a statistical result in a secondary format (such as a blog post) you can be affected by the writer’s own interpretation and packaging of the result.

It’s very educational to apply this concept to scientific studies / claims you see in your own life, both for how scientific studies are created (or fail to be created) and for how the results of those studies get to you (or fail to get to you)!

Information Digestion - What are your own Biases?

Let’s start with an estimation practice.

1. What’s the average number of books an American reads per year?

Now, let me ask another question. The twist is… you are allowed to change your answer for #1 based on your thinking here. (if you do, write down the change).

2. What’s the average number of books you read per year?

For now, notice how you felt answering these questions. We’ll return to this exercise and how you felt a bit later.

If phase 2 (transfer) mistakes come from society introducing bias in transferring information to us, then phase 3 (digestions) mistakes come from us having bias in consuming the information!

For this purpose, the best question I can find that I can ask myself is:

“Am I believing [X] because it is what I want to believe, or is it what I think is actually true?”

This question is not limited to the “digestion” phase, because it is relevant to all sorts of thinking and decision making! And… you guessed it, I also think of this as a type of selection effect. If we are biased to only listen to a certain kind of information but automatically ignore opposing information, we are hurting our ability to understand the world better given new data.

If I could coin the term “The Fundamental Forecasting Error” I would probably define it “believing in things that you want to believe as opposed to things you want to find the truth of.” Within this, I think there are 2 separate types of errors:

- Believing in the thing you want because you wish to live in a world where it is true (for example, maybe you want to believe an infectious disease is not serious, because you want to be outside freely without worrying about the disease.

- Believing in the thing you want because it was your first instinct and you don’t want it to be wrong (for example, maybe you want to believe an infectious disease is serious, because you told your friend group that they will all get it, and you don’t want to look “dumb” even though none of them got it after 5 weeks.

Let’s now apply this question to the previous exercise.

- When you gave your answer in part 2, did you change your answer to #1? Why did you change it?

- In particular, did you change your answer for (1) to be lower / change your answer (2) to be higher? If so, do you think part of it was to be “more well-read than the average American?”

You can go to Pew Research for some data on how much Americans actually read each year. Make your own conclusions!

But more importantly,

What are possible sources of selection bias in this Pew Research Survey?

Conclusion

In this “street fighting” lecture, I gave a model of how information gets to us and how it interacts with different types of selection effects. The concrete questions we can ask ourselves to better understand the information are:

- When the statistics was done, what was the population being sampled? Is there a selection bias?

- When I got the information, who told me the information and why? Would there be reasons that opposing information wouldn’t get to me?

- When I saw the information, how did I react to it? Am I believing [X] because it is what I want to believe, or is it what I think is actually true?

I’ve focused on things I’ve found personally useful, though there are already many presentations in both popular and academic literature about these topics. Some very well-known entries into the ideas are:

- How to Lie with Statistics, a very early popular treatment of how statistical packaging can lie

- Trust me, I am Lying, while I am certainly sure that parts of this book are itself lies, it seemed to have mostly stood up so far.

- Statistics Done Wrong is a slightly more technical introduction to the main “processing” parts of statistics done wrong, such as p-hacking, “researcher degrees of freedom”,

- Ioannidis’s Why Most Published Research Findings Are False is a seminal paper on “bad research” in academia; doing a “meta statistical analysis” on statistical analyses in search of anomalies.

- to iterate, it is also both fun and educational to look at discussions that look for weaknesses in this paper, such as Ioannidis (2005) was wrong: Most published research findings are not false. The rabbit hole is deep!

(I thank Collin Burns and Jacob Steinhardt for extensive help with this post. I thank Alex Lawson and Linch Zhang for valuable conversations.)